I remember a particular day in Sunday school when I was around 12. We were doing an activity that involved ranking which aspects of Jewish identity were most important to us. The point of the game was to examine the parts of our religion we’d be most reluctant to give up in the face of state repression. What would matter most to us in the ghetto? Some of the categories were Jewish music, reading Hebrew, observing Shabbat, etc.

I’m not sure what I said was most important. Maybe the music? Certainly not sitting through any sort of mind-numbing service. Maybe I said my ‘Jewish community,’ but that would have been disingenuous. Honestly, I remember thinking that if the Nazi’s came calling, I wouldn’t find it too difficult to give up the whole thing.

I never fit in well with the other Jews. I remember having just one friend in Sunday school, and together we would run headphones through the sleeves of our hoodies, listening to the same emo bands on our iPod Nanos, resting our heads against our palms surreptitiously during services. I don’t remember his name, but I’m grateful to him for showing me the headphone trick. If any spirit moved me during this time in my life, it wasn’t any incarnation of the ancient Jewish god, nor any innovation of reformism, but the Say Anything song that I had on repeat my 7th grade year.

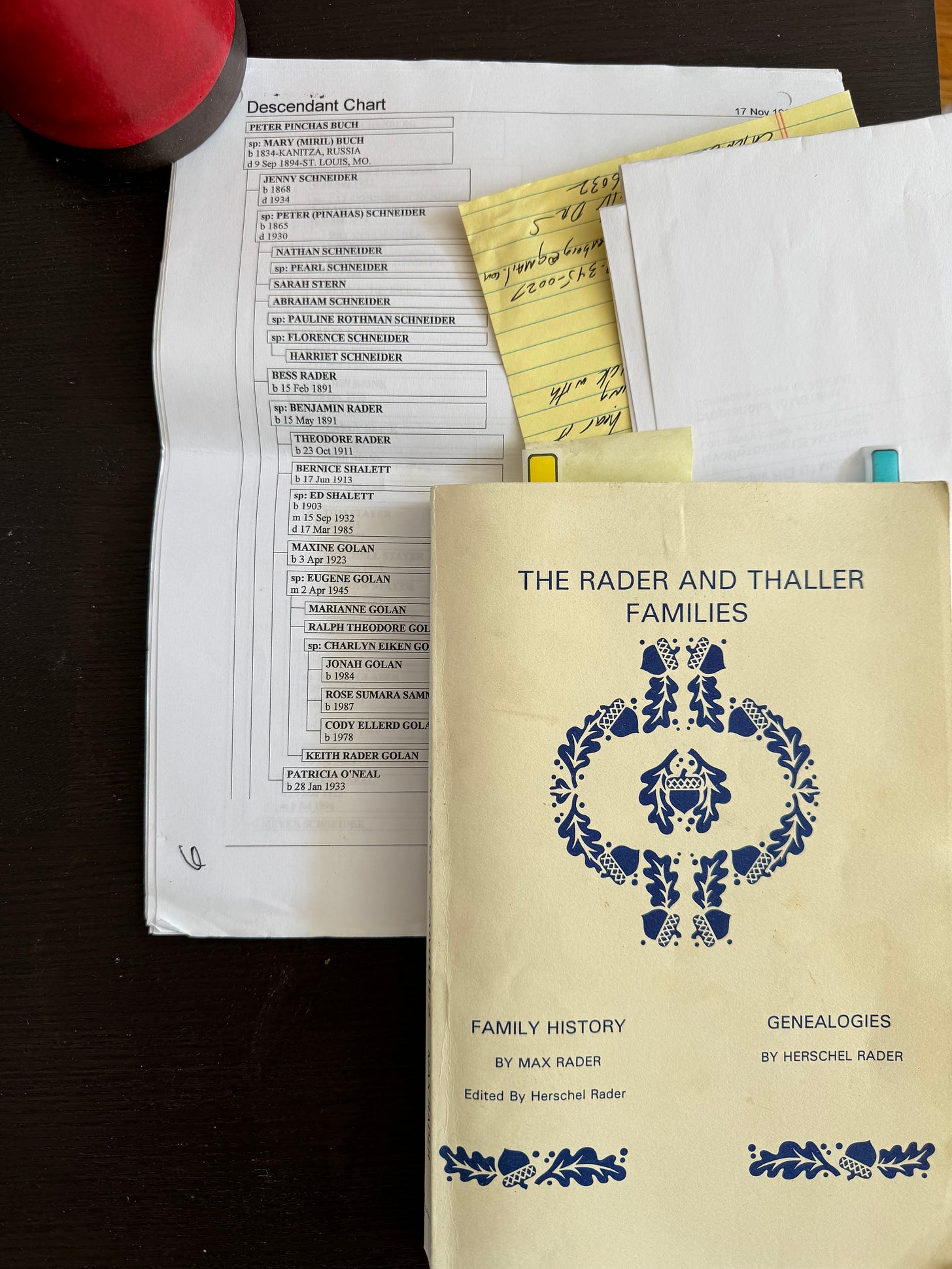

My family emigrated from what is now the Ukraine at the beginning of the 20th century. Their story is documented in a typewritten book I was lucky to get my hands on last year, an oral history recounted in the 1980s by the last survivors of the emigrant generation. They came from Filvarkis settlement – a real shit-hole as far as I can tell - in the western countryside. My family had the slight advantage of rudimentary education over the local Slavs, those same people committing the pogroms that would empty the countryside out of Jews. My family was forced to flee after an altercation between some great-uncle of mine and two local Slavic men. With a notice on my uncle’s life, he fled the country. The rest of the family followed shortly after, sneaking across the border past Lviv.

This was at a time in Tsarist Russia when Jewish boys as young as ten were sent to the frontlines to become cannon fodder. It was commonplace for mothers to maim their young sons to get them out of military service. This was the case for at least one of my uncles, whose disabilities were a liability in the immigration process. My family sought the most lenient checkpoints to smuggle across the half-blinded boy. For this reason, we entered through Baltimore and not Ellis Island. We went to St. Louis and later New Orleans and Chattanooga, a family of musicians and petit bourgeois, earning a southern drawl instead of the classic Brooklynese.

The oral history explains why my family looks more gentile than the average member of the tribe. A couple generations back, we were even blond. It’s not a happy reason, and it involves those same Slavs and what they did to the women of my family. It’s distant history, and there isn’t a record. Some goyishness forced its way into the gene pool.

I continued the post-Bar Mitzvah classes at my temple for a year or two - longer than either of my brothers. I liked the scholastic element of the faith, the prospect of an in-group intellectualism. I still felt on the outs for reasons I could never fully place. I never really believed in any of the religious shit, but that wasn’t the point anyway. The point was being cool enough to canoodle with a Rachel or a Sarah or a Rebecca in an empty classroom.

When I was in college, I started attending Chabad services (you can’t say I didn’t try!). That’s where the ‘cool’ Jews went, where rabbi would pour his cup of wine all the way full and chug it in between strange incantations. I was a long way from the woke cantor of my childhood, her (her) kapo-ed guitar. This wasn’t all that different from what we did in my fraternity. Some of the girls complained about the fact that Rabbi wouldn’t shake their hands (Chabad being a Hassidic organization), but we let it slide. Rabbi did Crossfit and chugged wine and had 7 kids. Rabbi fucked.

I went to Israel with that same Chabad group. Birthright was my first time leaving America. I was going with the popular Jews, those from cooler fraternities and hotter sororities and who had certainly left the country before. Suffice it to say I spent my time with Zev and Matt - two anemic intellectuals - cracking stupid jokes to each other and NOT talking to the sexy IDF soldiers.

It was a cursed trip. I got violently ill on the second day, and I spent my time at the Dead Sea slouched miserably under an umbrella watching bikini-clad girls smear mud onto the boys’ muscled chests. I got my revenge when the rest of the group got sick a few days later, leading to a memorable episode of vomiting in the Bedouin tent that sent three girls to the hospital to be put on IV drips.

Since the trip was organized by Chabad, our guides were two Modern Orthodox Israelis. This meant gender segregated Shabbat services and an evening lecture in which we learned that Palestinians do not exist. Our group bristled at these things - if we were to be Zionists, we could only be liberal Zionists. We should have been getting the soft, Tel-Aviv-flavored variation, with lots of alcohol and sex. A rueful talk on a two-state solution would have been better propaganda. This religious shit was too much - didn’t they know that?

But we ended up getting rather biblical with it when it snowed two feet toward the end of our trip. The most snow since 1950, we were told. Stranded in our hotel in Jerusalem, we drank Arak from the bottle and scavenged for food. I was in dire straits - I hadn’t been able to stomach the heavy, salty Israeli fare since my illness, and the liquor didn’t sit much better with me. Matt and Zev and I sat in a bathtub together, warming our numb feet and nursing the licorice booze. We cursed the first Jews who thought to come here. This was not our place - I felt this instinctively, even if it took another decade to catch up intellectually.

I never went back to Chabad after the trip. My interest in the faith waned, and my own status as a Jew retreated to a sort of default zone.

The other night, a friend of mine mentioned to me that he had stopped identifying as a Jew. He said nothing remained for him there after he was ostracized for his support of Palestine. I asked if there are anti-Zionist congregations. “One,” he said. “And they have to rent the space from a conservative church.”

It had never crossed my mind one could stop being a Jew. Frankly, that’s probably because I aready felt somewhat outside of the religion, my Bar Mitzvah and circumcision aside. Much like the flights out of snowy Tel-Aviv, my Judaism never really got off the ground. But everyone knows that you don’t have to believe in g-d or keep Kosher to be Jewish. We have Larry David and bagels with lox, dark hair and pale skin, neurotic mothers and tarnished kaddish cups and a reluctant kinship in common. But if being Jewish is just a question of community, and the community is by and large supportive – whether passively or actively – of the genocide in Gaza, in what way can I claim the faith of my ancestors? Do I even want to?

Am I a Jew because my distant grandmothers were raped by Goys? Because my less-distant grandfathers escaped Pogroms? I’d like to think I’m a Jew in the ways that Jews once were a sort of Bundist or socialist vanguard, inherently politically radical. But long before that – all the way back to the destruction of the 2nd temple – our people have had an ontology of suffering. Judaism exists in relation to persecution. For most of history, that persecution was our own, but now, we have become the persecutors.

It makes me physically ill to watch the footage of settlers attacking villagers in the West Bank, let alone the gruesome images of an endless, senseless campaign to end life in Gaza. I had to make myself watch the testimonies of those doctors who tended to children systematically picked off by snipers in Gaza. A bullet for every brain. And always there are the IDF soldiers wearing yarmulkes, the flag stitched into their uniform bearing a star of David in the middle, the familiar symbols of Judaism adjacent to the most despicable forms of violence, the most inhumane degradations.

As Brace Belden memorably put it, to be a Jew in America now means to be a sort of ‘super-white,’ and criticism of the state of Israel is now an offense that can lose you your job, your college degree, your freedom. Combatting antisemitism is the catchword for this round of fascism. This is, of course, the natural conclusion of a process of historical remembering that claims that a holocaust is something that can only happen to Jews, that Jews must always be the victims. No amount of death and destruction can unstop the ears of those who know their faith only in terms of their own historical persecution.

I am not beholden to some delusion of vengeance on the behalf of my raped ancestors any more than I’m beholden to the idiotic hatred in the heart of my ancestors who were doing the raping. Yet I see Jews around me clinging ever harder to their belief in team sports. Part of me gets it: when the scales fall away from your eyes, the reality is too horrifying to confront. Blindness is often easier.

I am not inclined to renounce my religion, even though I don’t believe in the Old Testament god (who could?), even though the majority of my brethren support Israel to this day. As much as I wish it were otherwise, Israel is inextricably tied to modern Judaism. Powerful actors have made it so, and you cannot be Jewish today without having a posture toward the Jewish state. Certainly, you can’t be a secular Jew, a Jew by way of community association and cultural heritage, without responding to the political reality we find ourselves in. In fact, I see now that I must remain a Jew specifically because my advocacy might, in some small way, be useful to the Palestinian cause. In a long history of rapes and lynchings and forced migrations, this is the latest chapter. It is contiguous with my own family history, even if it is Jews who are now the ones doing these things.

To return, then, to that Sunday school class: what would I give up? I have a better idea now: I won’t give up my values, my belief in justice, my ability to think for myself. I think it’s too easy to throw our hands up. To see what is being done in our name and to say ‘fuck all that.’ Especially since it’s those people who always seemed to belong more than me – in Sunday school and in college and on my Israel trip – who are now the most bloodthirsty, the most genocidal, the most insane. I understand the impulse to cede territory to them, those who probably think of themselves as the ‘real Jews.’ I won’t though. For the first time in my life, I feel genuinely stirred by my religion. I feel faith, and it is the belief that the struggle for liberation goes through Palestine. The belief that, once again, the axis of history turns on the Jewish people.

It's a bad question, lacking in nuance and wielded like a blunt weapon, but it’s the question we are being asked: will you back the genocide, or will you fight it?

I love the nuanced complexity of this post. And as always love your writing, Robbie.

This really moved me, I’m glad to have read it. Thank you for writing it.